Ok, so the question might seem a little strange, but if you think about it, we all know someone whose passport is full to the brim with stamps from foreign lands or a friend who brags about how many countries he or she has visited. Keep the word “dromomania” in your head. You’re going to hear about it quite a lot.

If we look at the traditional definition of “addiction”, any dictionary will tell us that it’s the state of being “physically and mentally dependent on a particular substance, especially drugs”. Have a think about whether any of your travel-loving friends might fit into that definition.

If there is one trend that has permeated the marketing departments of the biggest companies in the world, it’s the fact that the concept of material consumption has moved into the area of immaterial experiences. That might sound like marketing jargon, but it’s basically the trite concept of “experience marketing” and, within this area, one of the biggest thrills a person can purchase is the act of travelling – and the further, the better.

The problem arises when travel turns you into a sort of pathological tourist, becoming one of a growing number of “competitive travellers” whose only objective is to have visited more countries than any other person on the planet. That’s when the term “dromomania” comes into play, a word the Merriam Webster dictionary defines as “an exaggerated desire to wander.”

The word is new to us, but not the concept – we’ve all been a victim or a witness at some point. Everyone wants to travel, and frequently. There’s often an impulse to leave the country of our birth, travel the globe, get to know other cultures, foods, landscapes, smells, feelings and, above all, to photograph it so we can share it online. The traditional method of torturing friends who visit with photo after photo of your last trip has been transformed into a constant hammering via multiple online platforms with information that is now at our fingertips.

One of the main symptoms that someone has fallen victim to dromomania is the internalisation of another term that we bandy about every time we talk about going on holiday – the selfsame “break”. But before we get to talking about the historical and medical motivations that cause this condition, we’ll run through some more indications that you might be suffering from this addiction.

You spend hours and hours reading travel blogs or looking at travel accounts on Instagram. You pass the time between trips by planning another. You know all the main airports in the world – names and IATA codes. Your house is a shrine to souvenirs and keepsakes from past trips. You are an expert at maximising space in your suitcase. Your bank balance is always a bit precarious. You have at least one currency converter app. You can fall asleep whenever wherever. You’re a huge fan of “The Beach” by Alex Garland. And so on, ad infinitum.

Looking at dromomania once more, we want to know if travelling can really become an obsession, rather than something relaxing and enjoyable. It’s 1886, and we’re in Bordeaux when, suddenly, a young Frenchman called Jean Albert Dadas, reaches a hospital in the city exhausted and unable to remember how he got there. He knows only that that he travels great distances every day and that, for him, this is normal.

The 26-year old worked at a gas company in Bordeaux itself and had always suffered from a somewhat unusual disorder: sleepwalking. His attacks came on suddenly and infrequently. In his semi-conscious state, he would feel a strong need to travel, forgetting his friends and family and even taking on new identities as he moved around randomly without stopping.

After a couple of weeks, he would wake from his trance and return to his normal self, rejoining his home, his work, and his life. He had even woken up in places like Prague, Moscow, and Algeria, without really knowing how he had arrived there. Dadas was the first pathological tourist. And all this happened in a time when the concept of tourism was restricted to the upper classes of society.

The strange case of Dadas was studied by various psychiatry specialists of the time and one of them, Philippe Tissié, carefully proved that Dadas had indeed travelled to the places he claimed, having made contact with consulates and places Dadas had stayed to confirm it. He discovered that Dadas had suffered many hardships while on these journeys, having spent time in prison for begging more than once, and in hospitals, suffering from exhaustion.

Several years later, Tissié wrote a thesis describing the disorder, calling it dromomania or ambulatory automatism. We’re not sure if any of our compulsive or competitive travellers suffer from this illness, but the term is definitely being used to describe the obsessive nature of the behaviour in some.

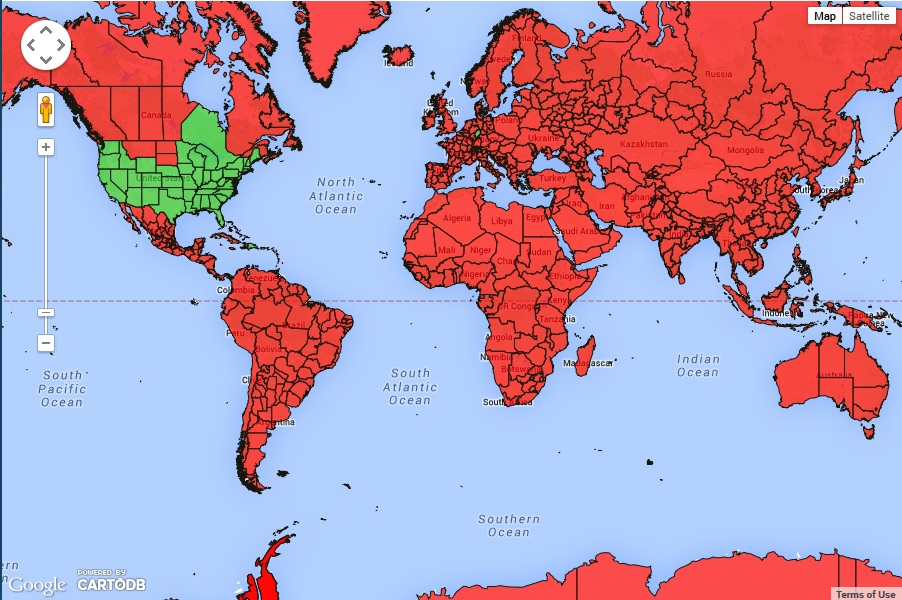

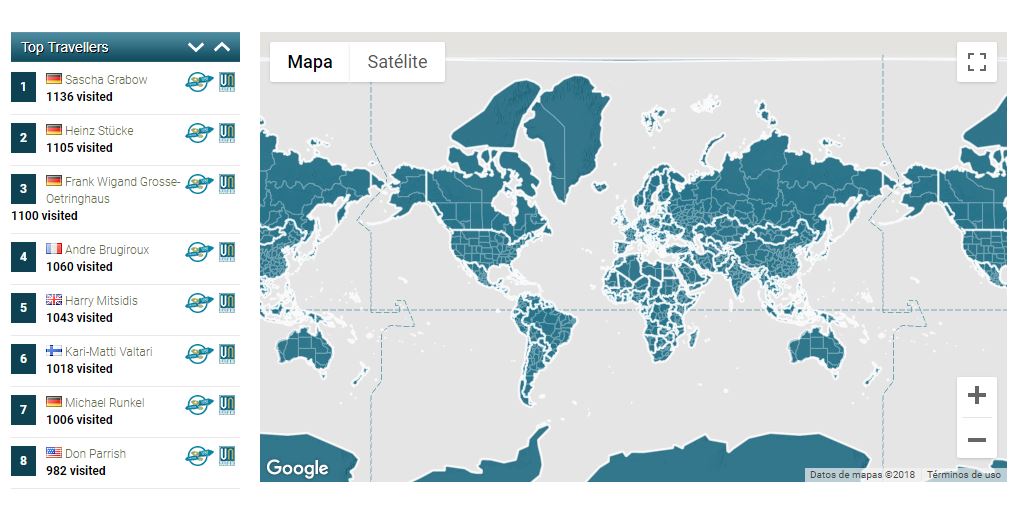

The race to “get to know” more of the world than other people has given rise to the creation of many websites that list rankings and classifies overwhelming data to establish who is the planet’s “best” traveller. They are real sites where somewhere around 30,000 people compete fiercely to add points to their account and become the leading hyper-traveller in the world. Website like Most Traveled People and The Best Traveled document this competition, as do apps like Been and Countries Been.

Maybe the dromomaniacs of our time are hidden within the rankings on these websites. No, in fact, we’re sure there’s more than one. Their trance would be more controllable and buying a plane, or train ticket is their equivalent of shooting up.

This can become dangerous, as you can see when you take a closer look at the social media profiles of some of these “competitive travellers”, and you see how on more than one occasion they’ve put their life at risk to reach a conflictive destination or lost contact with friends and family in the fight to become a super-traveller. We won’t mention anyone specifically, but if you take a look around some of the sites we told you about earlier, you’ll be able to find them easily yourself.

Many of these people show a constant feeling of dissatisfaction and emptiness while at the same time provoking familial and professional conflict, and almost all of them have posted a picture on Instagram where they declare that they have not yet “found themselves”. We don’t know about you, but to us, that sounds very much like our good friend Dadas…